People are resistant to change; teachers are no different.

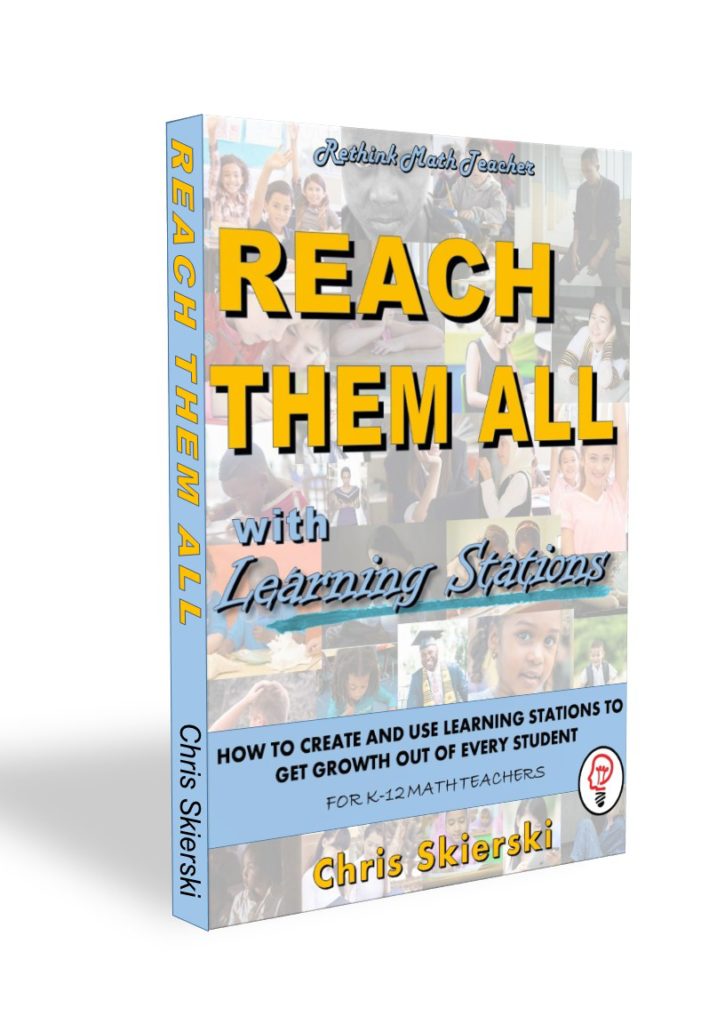

When a teacher first hears me talk about differentiated instruction, and how I create learning stations and activities to remediate each student based on what skill they need to develop to be able to do the grade-level work, most teachers say the same thing to me, “It can’t be done!”

Isn’t it funny how often we as teachers act like our students?

I once went to a math training at our school district and sat in a room with other educators. The presenter began the training with a math puzzle, asking us to figure out how many of a certain type of card there were if we mixed decks together. The vast majority of the teachers all shook their heads, made an excuse about how tired they were, and refused to participate.

I’ve sat through many presentations and trainings, feeling sorry for the presenter trying to speak over a room full of teachers who would not stop talking to their peers seated next to them, despite several requests from the stage for them to stop.

Why It Can’t Be Done

As stated above, teachers are very quick to tell me that what I’m doing in my classroom can’t be done.

We would never accept such answers from our students. If you asked a student in your class to do something (mathematically) and they responded, “I’m not a math person,” or “There’s no way to solve this problem,” you would have a fit!

I’m sure you would motivate that student, push them, and challenge them; all the while being frustrated at their close-mindedness.

Having a Growth Mindset

Most students don’t have a growth mindset because most people don’t have one. This is why most teachers don’t have one either.

When I tell teachers that they should reach every student in their class by differentiating their instruction to target the skill that student needs remediating to help them get to grade level, I’m met with all sorts of closed-minded answers: “How would do grades?” “How would you submit lesson plans?” “The district says I have to get through the pacing guide, you can’t if you spend all your time remediating students.” And on and on the list goes.

There’s a million reasons why you can’t do something. But the biggest reason is because it’s different.

“You’re asking me to grow. To try something new. To change.”

The Education Delusion

As educators, we like to think that we’re operating within the correct confines of the situation, and only minor switches need to be made to achieve perfection.

Educators are always asking things like, “I’m looking for a good activity to help my students learn such and such.” OR “I’m looking for a good illustration to help my students get this and that.” And while good instruction, illustrations, and activities definitely help, they are not the fix we need.

If there was a magic way to explain a certain concept that would help every student grasp it, in the thousand of years we’ve been doing school, someone would have figured it out by now and fixed everyone’s issue. But we still have students in high school who don’t know their times tables, need their fingers to subtract, and don’t understand how to plot a point on a coordinate plane.

Return to Basics

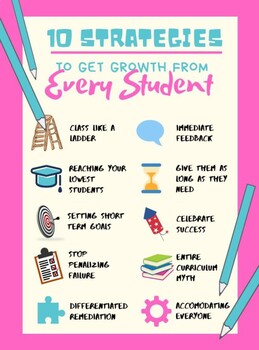

Minor changes are not needed. Instead, a return to basics is required. Simple teaching strategies that work.

Do you know how to do something? Play the guitar, swing a golf club, ride a bike? How did you learn it? You were shown how, then you were given lots of practice with feedback when you failed until you mastered it.

We’ve been teaching children how to ride bikes for decades with no revolutionary new strategies. Just simple, time-proven methods; model, practice, guide, correct, repeat. Repeat until you get it!

Why Differentiation is so Effective

If you’re teaching students how to add fractions, but they still don’t know how to convert fractions to common denominators, you need to first teach them this necessary prerequisite skill. You can continue to model to them how to add fractions, but they will never understand it until they grasp all the skills needed to master this concept.

So instead of teaching adding fractions over and over again, I propose that you show them how to convert fractions into common denominators.

BUT! What about the student who knows how to convert fractions to common denominators, but they don’t know how to add fractions? I would recommend that you don’t remediate that student on finding common denominators, instead allow them to work on adding fractions.

AND what about the student who has already mastered adding fractions? I do not think it would be in that student’s best interest to keep him working on adding fractions when he’s ready to move on. Instead, accelerate him to the next skill.

By doing all of the above, at the same time, you will need to differentiate.

One student needs remediation, the other needs to work on adding fractions, and the third needs to be accelerated to the next skill. The only way to reach all of the students is to differentiate your instruction so that you are meeting the needs of all three.

Uncommon Teaching

To differentiate in the way I have outlined in the above section, you have to do things differently. You can no longer give one tutorial to the whole class, at the same time, with the same number of problems and then promote them all to the next skill together.

That’s what is commonly done. And it’s not effective. In that scenario, your weaker student who needs remediation isn’t given it. Instead they are drug on to more challenging work when they are not ready, and will continue to struggle. At the same time, the stronger students are forced to stay back when they need to be pushed ahead and challenged. Thus they become board and can also become a behavioral issue.

Want to Learn More about Differentiated Instruction?

Read these articles next

- 7 Reasons Why You Should Differentiate

- What is a Skills Based Learning Station

- Differentiated Remediation

- How to Teach Your Students to Learn from Their Mistakes