I often hear teachers complain that their students say that they want an A in their class, but they’re unwilling to do the work necessary to earn it. Even when they are capable of doing the work, they still get off task or misbehave. How can this be when they know it will cost them the A they claim to desire?

An Illustration

I have three small girls at home. At the time of writing, they are six, six, and seven years of age. This past weekend we had an event to attend, that they were very excited about and did not want to be late to.

So 10 minutes before the time we were supposed to leave, I told them to go to the restroom and get their shoes on. You would think that 10 minutes was enough time to accomplish these two tasks, but you would be wrong!

On the way to the restroom, one sees some of her toys that she would like to bring to the event. So she grabs them, brings them to me, and asks if she can take them to the event. “No,” I politely say, “you don’t want to lose them. Plus there will be lots of things there to play with.”

She begins to cry and falls on the floor.

Meanwhile, my second daughter, on her way to the bathroom, has spotted the mirror and is now standing in front of it making faces.

The third cannot find her shoes.

I gently remind the second to go to the bathroom and tell the third to check on the porch for shoes. But when she gets out there, she sees something she was playing with earlier and starts playing with it – instead of looking for her shoes.

The first still on the floor crying.

I put the first in time out for her fit since rationalization has not worked with her.

I grab my second child by the hand and escort her to the bathroom, demanding that she use it. Then, I take the third girl outside and point to her shoes that she has so inefficiently looked for.

A few other similar incidents have my blood boiling, and I sit all three down for a heart-to-heart conversation. I reminded him that we are trying to leave to go to this event, and if we don’t all go potty and put our shoes on quickly, we will be late.

“Do you want to be late?” I ask. “No,” they all say. Then I beg them to go to the bathroom and put their shoes on.

Before anyone has left, the first has asked me if she can bring a different toy, and just bring it in the van for the trip. The second here’s this and shouts “No fair! If she brings that, I want to bring this.” The third also has her demands.

“Nobody is allowed to bring anything!” I say (maybe I shouted). “There will be toys and activities for you to play with there, and we don’t want to lose our toys.”

All three look at me very sad, and start to cry.

They’re Just Children

While the above scenario is frustrating and common in our house, I have to remind myself that they are just children. Their brains are not fully developed and they are not capable of thinking long-term. Their immediate desire to play with a toy or stare at themselves in the mirror is a more powerful desire than their desire to put on their shoes. Even though putting their shoes on will result in a timely arrival to the event, which will be more fun than doing those other things, they are not capable of allowing such rationalizations to overpower their immediate desires that come with instant gratification.

The Problem of ‘Instant Gratification’

I remember watching a news report a long time ago where they would put a child in a room with their favorite candy. They would tell the child if they can wait five minutes without eating it he will get more of that candy than he already has. Almost without fail, the children would eat the candy that was in front of them even though they knew if they waited they would get more than the one piece.

The students in your classroom are no different. They’re not capable of rationalizing long-term consequences. Yes, they want an A on their report card more than they want the other grade options.

But the report card is nine weeks away. And today, their friend is sitting next to them and there’s something on their minded like to share. Or their cell phone is buzzing in their pocket. Or they’re tired. Or there’s some new drama with some students in their class. Or a litany of other items that are more entertaining or have more instant gratifications than completing the work in your class.

That short-term reward has outweighed the long-term reward of a good grade in your class.

They’re young. They don’t have the maturity to consider the long-term and make it outweigh the immediate benefits in the short term. They can’t even consider weeks away.

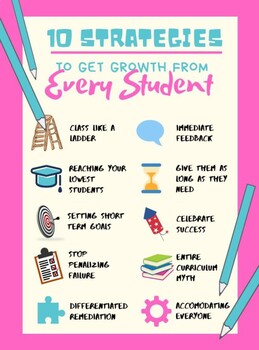

So what can we do?

Whenever I am meeting with a parent about their students’ grades or behavior, I often hear them tell me that they have taken away their child’s toys, games, phone, etc. until the student brings home good grades on their report card. While I am glad that they are implementing consequences and placing a value on the student’s education – they have also robbed the student of any hope of getting those items back.

As already said, the young person cannot consider 9 weeks away, its too far. There are too many obstacles between this day and that one, and the student eventually will give up hope and not care about ever getting those items back.

I instead encourage the parents to set up some short-term goals, with some short-term rewards. For example, if they complete all their homework this day or week, then they can earn a few hours of screen time this weekend. Or if there are no grades below a C this week, they get some easy reward on Friday night. I encourage the parents to set some short-term goal, that’s easy to know if they have obtained it, with a short-term reward.

This concept can work in your class as well

Set up short-term goals with short-term, easy to achieve rewards.

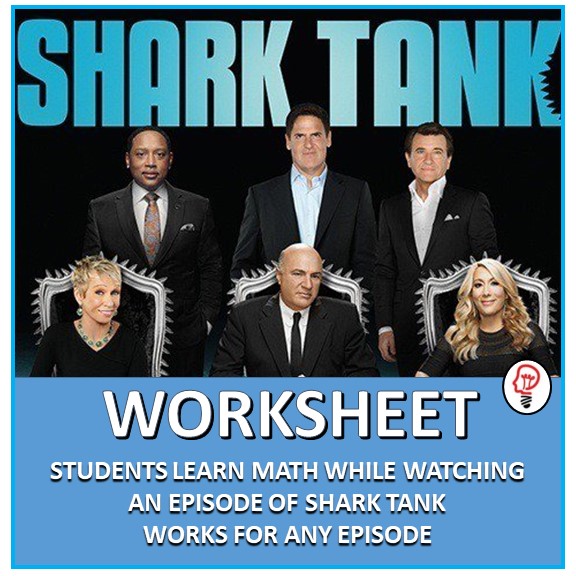

For example, I used to challenge my class that if everyone in the class completed their homework (just completed it) that we would spend the last 10 minutes of class watching Shark Tank!

(Mind you, when we watched ABC’s hit reality show, Shark Tank, we did a Shark Tank Worksheet with it and did lots of math problems from the segments, but they still loved watching the show and got to see practical applications of Math).

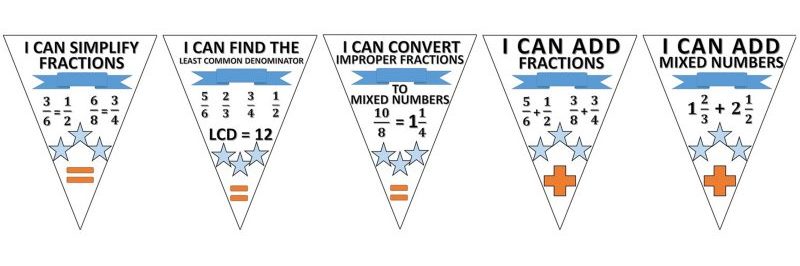

I also use 3 Day Learning Stations to accomplish this. I build stations on different skills that my students are struggling with. I put each student in the station of the skill that they need to work on, and they work on that station for three days. At the end of the three days, I assess them, to see if they have mastered the skill. If they have, we celebrate that success with a banner that we put in the room with the name of the skill they have mastered. We then put their name under that banner to celebrate their accomplishment and send a certificate or letter home to their parents.

Even my inner city middle and high school students love this corny celebration because it is a short-term reward that helps them understand that they have been successful.

And once they’ve tasted that success, they will want to repeat it.

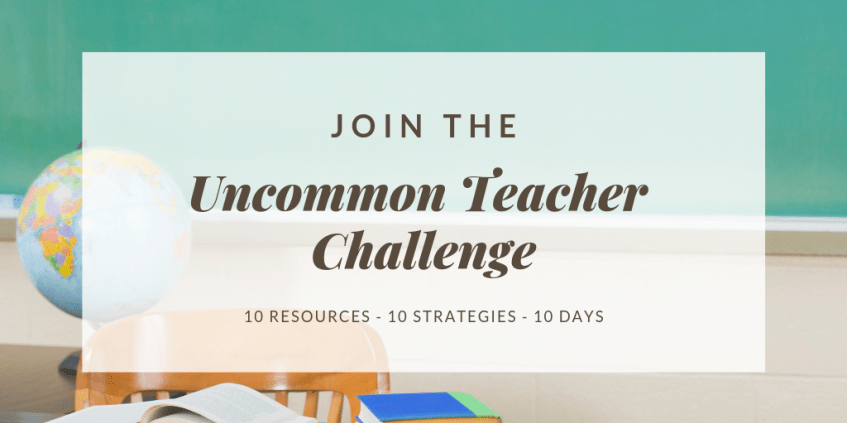

I am challenging readers of this blog, and followers of the Facebook page, to join me on a journey, where every week I will send them a resource to help them differentiate their instruction so that they can reach all of their students. I will be sharing a lot of information in the upcoming posts about the learning stations I just referenced above.

Every week I will also be giving away a free resource to help you on this journey.

This week’s free resource is a PowerPoint slide that will allow you to build your own pennants so that you too can celebrate your students’ success.

an example of how I use pennants in my class

Click here to download the PowerPoint slide to get the pennants above that you can edit for whatever skill your students are working on.

The email will come within minutes, so check your primary and promotional email inboxes. Then mark as safe – because more resources will be emailed to you in the weeks to come.