I’m a big promoter of not trying to cram the entire year’s curriculum into all of your students.

Many of your students are entering your class below grade level, and it is not reasonable to think that they will be able to get caught up to being on grade level, and also learn the entire year’s worth of curriculum in the same year.

Some of your students are on grade level, or higher, and by all means, push them to grow as much as they can. But for your weaker students, the goal should be growth, not exposure to a year’s worth of content.

Furthermore, some of your students will take longer to grasp a concept, or need more practice repetitions than their peers. It would be far better to allow them this extra practice so that they can obtain mastery, then to push them further into the curriculum. This would result in them seeing more math concepts but failing to master them.

Tell that to the Test Makers

The most common objection that I am met with when I advocate for such pacing, is that I (the teacher) can’t do it because I am accountable to the state test – and that test will ask questions from the entire year’s worth of curriculum.

Dear Teacher, you have totally missed the point.

Here’s the Point

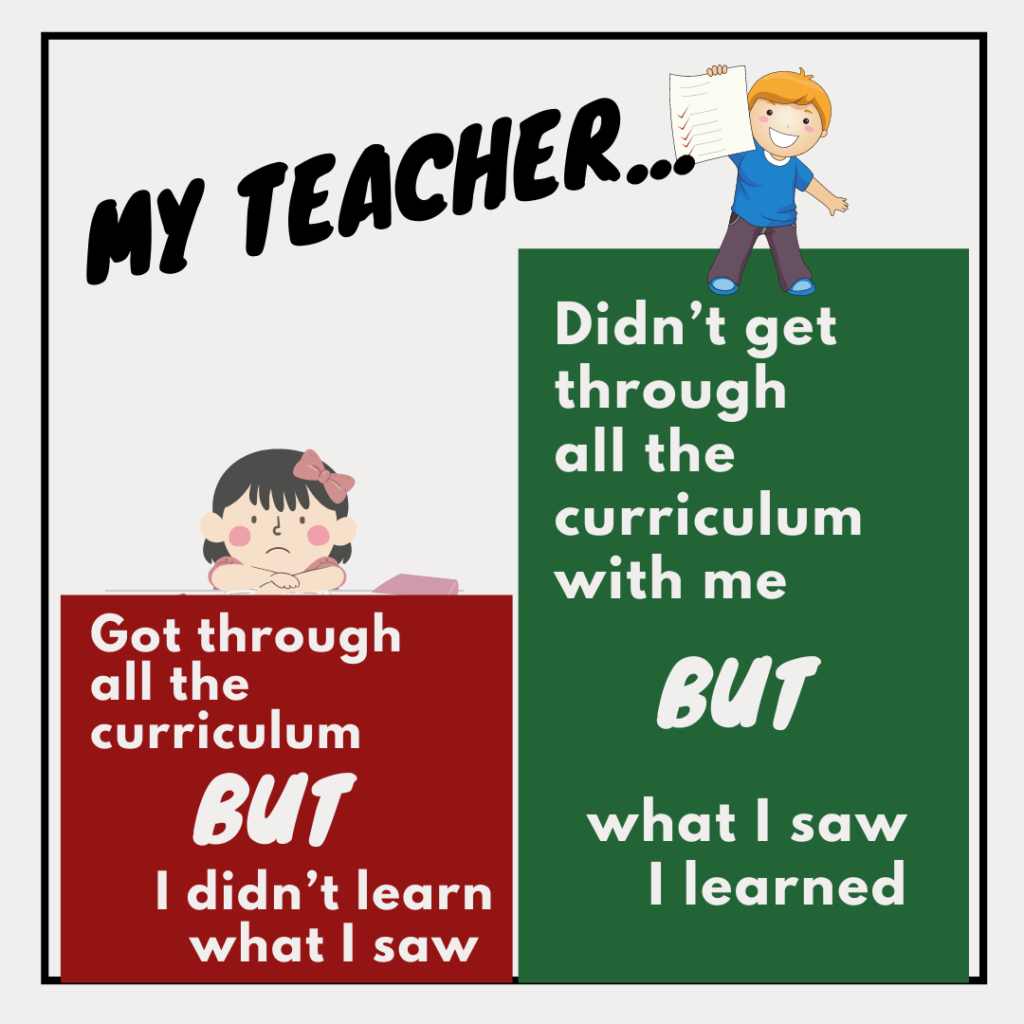

Let’s look at two students. Both are below grade level. We’ll call them Sussie and Bobby.

Susie’s Journey

Susie is in your class, where you believe that you must show her the entire year’s worth of curriculum because she takes the state test. So you show her every standard. You cram the whole thing into your instructional design in one year.

Susie saw the first concept, but she failed to grasp it because it required knowledge of skills learned in previous grades – which she had not mastered. Instead of remediating her, you put her through the same lesson as everyone else, so she didn’t get it.

Then you move Susie on to standard two. She actually started to grasp it, but since she takes longer to learn than her peers, she did not fully master it before you again moved her on to the next standard. She got a C- on this test, which is good for her.

Then on to standard three, and four, and so on throughout the year. Susie is constantly pushed from one topic to the next without ever mastering one. She gets some of one or two standards, but mostly, she has failed to grasp any of them.

How do you think Susie will do on the test?

Considering she has not actually learned any of the standards you have exposed her to, she will do poorly. Likely testing in the bottom 25% of the state, and definitely showing no measurable growth.

She will not test on grade level.

Bobby’s Journey

Bobby is in my class. He will take the same test that Sussie will.

Before being taught the first standard, I give him (and his classmates) a diagnostic to see if they have mastered the prerequisite skills needed to do this standard. Bobby has not mastered any of the previously taught material, so I remediate him on each skill until he’s ready for the grade level work. It takes a long time.

The majority of his classmates have long moved on to more rigorous topics, but Bobby continues to master one skill at a time until eventually he fully understands the first standard. He aces his test.

He is now moved on to standard two (Sussie is already working on the fourth standard). Since this standard builds on standard one, Bobby has already been remediated and is ready for it. However, like Sussie, Bobby doesn’t learn as fast as his peers and requires more practice repetitions before he fully comprehends it.

No problem. I let Bobby work on this standard longer than the other students. He gets more practice problems than everyone else, and take two weeks longer than his classmates to learn the material.

Let’s pretend, for argument’s sake, that Bobby is only able to do one more standard before the end of the year.

The Tale of Two Students

So, which of the above students will do better on the performance assessment?

Sussie, who mastered none of the material, but got to sit in your classroom and hear about every one of them. Or Bobby, who did not hear about every standard. In fact, there are some standards on the test that he has never even seen. But he has completely and fully mastered three?

The correct answer is Bobby.

Bobby will show mastery on three standards, while Sussie will show mastery on none.

Let’s look at a real world example

If you have ever tried to learn a foreign language, you may have experienced difficulty. If it was difficult for you, then you can relate to Bobby and Susie above.

However, what is the better way to learn a foreign language, to hear every word in the language inside of a short period of time? Or to learn a few words, and master them, and then a few more, and master those, and so on?

How about teaching a young child to read and write?

Is it better to show them all the letters, and if they don’t know them, you move them on to blends and sight words? Or do you first have the child master all the letters and sounds, or at least the ones needed for the words you’re working on, before working on sounding out words?

Do you teach a student a song on the piano if they can’t play their chords?

Do you try to teach a young person to hit a fast pitch baseball if they still can’t hit the ball off of the tee?

In all of these examples, the answer is obvious. You don’t progress a learner to a more difficult skill until they first master the prerequisite skill.

The same is true in math. Students must learn the foundational skills prior to the more complex ones. And they must be given time and enough practice repetitions to master what you are teaching them.

And if, you move them on to the next skill without letting them master the one they were working on, theyresult will be that they will master neither; instead of both.

Exposure doesn’t Equal Mastery

In every area of life, we understand that simply showing someone something will not help them master it. They need to do it for themselves, practice it, commit it to memory for them to master the concept. Whether it’s swinging a hammer or reciting Shakespeare, this principle remains.

I don’t know why we think it will work differently on the state diagnostic.

Showing your students every standard on the test will not result in them being able to do the work when they take it. Instead, help them master as many standards as they can. Quality over Quantity.

If your student masters two or three standards he will do better on the diagnostic than if he masters zero but sees them all.

But the Diagnostic Tests my Students on All the Standards

Yes, the diagnostic will show them questions from the entire curriculum. However, they will only get points for the questions that they get right.

So, it is better for them to get a few questions right, than none.

This is why not all of my students will get to see all of the standards. In fact, some of my students will only see and do work on a few standards by the end of the year. But the standards they do see and work on, they will know and master. And they do much better than their counterparts, and than students all over the state, because they have learned some of the material – and they have fully mastered it.

In fact, my students far out perform the state average, even though my students start they year well below the state average.

How do I get students who are so low to perform so well? The answer is I let them take as long as they need, and I give them as much practice as it takes for them to master the one skill we are working on. And once they master it, we move onto the next (not before).

What about My Stronger Students?

The same concept is true for your stronger students. They should not be progressed to the next skill until they master the first. However, your stronger students will likely not take as long to master the skill – nor will they need to be remediated (or at least not remediated the same amount as your weaker students).

So your stronger students should be exposed to more of the curriculum than your weaker students. Some of your strongest students should be able to get through all of the curriculem.

Conclusion

If you agree with me, that it is better to show your students fewer standards and have them master the ones that you show them as opposed to showing them many and having them master none – then put your faith to action.

Do NOT say that you can’t implement this strategy because the state diagnostic will show them all of the standards.

In fact, the state diagnostic will prove this theory correct.

My students always do very well on the diagnostic, outperforming their counterparts in their school as well as in neighboring schools, as well as in schools across the state. This is because my students, though they are shown less of the curriculum than students in other teachers’ classes, actually master more of it.

Less is more.

The diagnostic will not penalize you for not exposing your students to every standard, in fact, the opposite is true.

Your students will perform better on the diagnostic if you let them master a concept before moving them onto the next before they are ready.

In conclusion, knowing that your students will be accountable to the end of your diagnostic, should encourage you. It should also strengthen your resolve to teach students in the most effective way possible.

If you let your students master all of the concepts that you teach them (even though you don’t teach them all of the concepts in the curriculum) they will do well on the diagnostic, and your classes will outperform others’ who try to expose their students to the whole curriculum without allowing them to master what they are shown.