Johnny walked up to me at the end of class. “Did I do better?” he asked, anticipating a positive response from me.

Recently, Johnny had been getting into quite a bit of trouble in my class. So much so that I had called home and issued some disciplinary actions. I should have been encouraged by his question. After all, his desire to know if he had improved meant that there was some support from his parents and that he at least felt like he had made an effort. Furthermore, his question meant that he wanted to do better.

Unfortunately, I was frustrated. “Seriously,” I thought to myself. I had to call his name several times for talking to his neighbor, he barely did any of his work, he needed constant redirection, and twice he got out of his seat without permission.

I wanted to voice my frustration at his misbehavior today, but something struck me by the word “better.” Had he made improvements? I wasn’t sure.

To be fair, he did comply when redirected, he didn’t write on his desk or on the wall, there was no profanity, he didn’t get sent out of the room, nor did he argue with me. So that was a step in the right direction. But I was also frustrated at how many times I had to remind him of the behavior expectations.

What’s Realistic?

If a student struggles with blurting out, and is constantly shouting things in class, is it realistic for him to be able to completely stop overnight?

Can a student completely change her behavior in one day? Especially if it’s a behavior she’s been engaged in for an extended period of time? (Almost as if it’s become her habit).

It’s probably more realistic that a student will make improvements as opposed to a dramatic change.

Is He Doing Better?

When the student came and asked me if he was doing ‘better,’ I did not know how to answer. I felt like he had, because he hadn’t done any of the large no-no’s. However, I also felt like he hadn’t, because I was frustrated with his misbehavior.

But did I have to redirect him less than the previous day? Less than normal? I wasn’t sure. And was this behavior better than previous days? Better than usual? I didn’t really have a way to know for sure. Thus, I was unable to give him feedback on his improvement (or lack thereof).

What I needed was a way to actually measure his behavior, objectively.

Working with the Student

Of course, we work with the student who is struggling. We provide feedback, redirect, remind her of expectations, change seats, give work accommodations, and the list goes on.

What’s normally missing, however, is a way to celebrate a student’s progress.

Often, the student is trying his best, and making growth, but it is unnoticed because his improvement has not brought his behavior to where it should be; or because we are so accustomed to her misbehavior that we exacerbate the issues that do occur, even though progress may have been made.

The Power of Celebration

Most people respond well to positive reinforcement.

I was always amazed at how I could get a room of urban high school students to be quiet by simply complimenting, and thanking, those who were doing what they were supposed to – the others, seeking that positive affirmation, typically complied.

If we are constantly berating a student who is trying to make improvements, but struggling to control himself, he is likely to give up or lose motivation. If instead, we celebrate them when they are performing as expected (even if it’s on a simple task or for a short period of time) we are much more likely to encourage that student to do better.

Our school once had an elementary student who could not stay seated during ‘carpet-square time’ (when students are assigned a square on the carpet so that the teacher can read a story to the class). Every day he failed to stay in his square and would subsequently get in trouble. However, one day, after much work from his teacher, he found success. He was immediately celebrated. He even got the ‘student of the week’ award. This positive reinforcement helped motivate him to do better in the days and weeks to follow.

A Helpful Strategy

Sometimes, when I have a student who is struggling with a specific behavior, we begin tracking it. In many circumstances, the act of keeping a record of the off-task incidents will help reduce them.

For example, I had a student who was constantly shouting out in class. So I put a sticky note on his desk, and he knew that anytime he shouted something out, he had to put a tally mark on it. Thus, we kept track of his ‘blurt-outs’ every day. Eventually, we set goals and gave consequences or rewards to him based on his goal and the number of tallies. As time passed, we lowered the number of blurt-outs he was permitted to reach his goal. In so doing, his behavior improved and we were able to notice it (and celebrate his success).

Action Plan

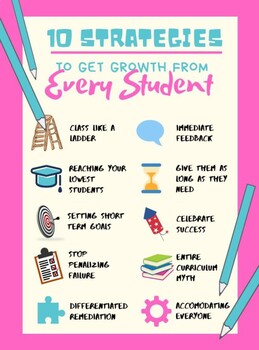

1) Identify the Behavior

If you have a student who is struggling with behavior, first identify the specific behavior that you want to target. Is he shouting out? Not doing his work? Throwing paper across the room? Getting out of his seat? Coming unprepared to class?

Make sure that the behavior is specific, measurable, and easy to identify. Don’t say ‘she misbehaves.’ That is not specific, nor can we measure whether or not it’s being displayed. Instead, the behavior should be specified as, ‘she talks to other students when she is not supposed to.’ Or, ‘she doesn’t do her work without having to be redirected.’

Likewise, the behavior should not be ‘talking.’ Because there are times in class when it’s okay to talk, and even when it is encouraged. So specify, ‘she talks to other students when she is supposed to be doing her independent work.’ Or ‘he talks when the instructor is giving instructions.’

2) Make the student and parent aware

After you have identified the behavior you want to correct (and you should not be working on too many at once. Depending on the age, it should be between one and three), you want to let the student and parents know that the student is struggling with this classroom expectation but you have a plan that’s going to help her find success.

The purpose of letting the parents know is so that they can support you and so that they feel that you are working to help the student, not simply discipline him. So when you call home, it’s just to inform the parent of your plan and seek their support. You don’t need to elaborate on how poor the behavior is or why it’s an issue, just tell the parent, ‘Johnny has been struggling to do such and such in my class, so I wanted to fill you in on what we’re going to do to help him be successful.’

You may also want to seek the parent’s help in providing positive behavior reinforcements (more on that in number 3).

You also need to make the student aware. Again, the purpose is not to shame her, or vent your frustrations, it’s to make her feel like you’re on her side and the two of you are working together. This will also help the student recognize when she is not meeting her expectations.

3) Set a Target

You need to set a realistic target for the behavior you want to correct. You can do this with the parent or student’s input, or without.

The target needs to be realistic, which means it most likely should NOT be zero.

For example, with my student who was blurting things out constantly through the class, we set up a goal of three blurt-outs per day. This was not easy for him to meet, but it also was still more than every other student’s quota. Knowing he had this target also helped him because once he hit two, he knew he only had one left before there was a consequence.

A quick aside, if the behavior is something detrimental to others, like swearing, antagonizing, or hitting other students, I do not recommend this strategy. These behaviors are not to be permitted and should be met with appropriate discipline every time.

Finally, with your goal, you should work through some rewards and consequences for meeting or not meeting the goal. It’s okay to be fluid on this – changing it over time. I like to get the parents help on the reward – like having the student ‘earn’ screen time over the weekend or be allowed to participate in some activity based on whether or not he met his goal.

Remember to keep goals short-term. Students cannot keep a goal that is long-term. I recommend the goal, and thus the reward or consequence, be no longer than one week – and maybe as short as a day or a class period. The older the student, the longer-term the goal can be, but for most age levels you should not be trying to get them to accomplish something for more than a few days – otherwise they will lose focus struggle to stay committed to their goals.

Thus, their rewards should not be anything big either. A few hours of screen time, a trip to the movies, or ice-cream after dinner are great rewards (for the parents, if you’re doing something in school it should also be small in scale).

I constantly have parents tell me that they took everything out of their student’s possession (phone, x-box, tv, etc.) and she can’t have it back until she brings home good grades on her report card. I always rebuttal that I appreciate the support and the focus on education, but that nine-weeks is too far away for her to focus on. This type of consequence (or reward) will not produce the intended results.

Instead, focus on good behavior or completed assignments for a day. And then, move it to a whole week. Start small, and make it easier for the student to both find success and stay focused.

4) Keep Data

Now that you have a defined behavior (or two) and a goal, you need to collect data. I create logs or tracking forms so that the student plays a part in the process. But as mentioned above, I have used sticky notes on desks too. (I’ll show you my logs at the end of this post).

Make sure to keep this data somewhere (usually a digital file will work fine) and share it with the student and parent(s) – especially when the student is making progress.

The process of keeping data will also help you determine whether or not the student is making progress (doing better). Then you can celebrate the student, or implement the appropriate consequences.

5) Celebrate and Adjust

As the student finds success, be sure to celebrate it with him, and his parents. Implement those rewards that you agreed upon. Beyond this, you should also be adjusting the goal. The student whose goal was to remain under 3 ‘blurt-outs’ a day, should be moved to under two ‘blurt-outs’ a day. The student who was trying to work for 3 consecutive minutes without falling off task, should now aim to work for 5 straight minutes without issue. And so on.

Some Resources to Help You

Both of the above resources are free when you purchase the book (below).

More Articles on Classroom Management

- Tips for Calling Parents

- Improving Classroom Management through Social Contracts

- Implementing Your Classroom Procedures

- How to Avoid Over-reacting to Students

- How to Decrease Off-Task Behavior

- The Uncommon Teacher Challenge

- 7 Positive Behavior Reinforcement Strategies

- 15 Strategies for the Student who Keeps Blurting Out